by Jenn

Before moving to Burundi, I would say I had a black thumb and knew nothing about animals. If I had read a book in the past 10 years, it was likely about the developing fetus, NOT how animals develop.

Three and a half years after moving here though, I can say that I have become a budding gardener, and have successfully watched the process of chicks hatching. I phrase the latter that way, because it's truly magnificent how LITTLE I contributed to the process of chicks hatching.

Maybe not all of you know, but about a year ago, just after arriving back from home assignment, I had a hen house constructed and brought home some cute 3-month old pullets.

Eight to be excact. But in a few short weeks, we realized that in fact we had one cockrel.

Two terms I learned at that time : pullet - a young female chicken who will grow into a hen. Cockrel - a young male chicken who will grow into a rooster. The girls named him Handsome.

Sadly, he became too lound and so he .... well, let's just say he's not around anymore...

The seven ladies grew like weeds and started producing eggs around 5-6 months of age. Which is pretty typical. Good job ladies. We have been enjoying lovely eggs for the past year. They produce 4-7 eggs/day.

One day a few months ago, I noticed one hen having some odd behavior. She was not leaving the coop and sat on all of the eggs all of the time. She would leave the coop maybe once to eat, drink, and poop, but otherwise didn't move much. I wondered if she was getting sick, but then a lightbulb went of... she's brooding!

Another term I learned - brooding - when a hen spends most of her days and nights sitting on the eggs in order that they may hatch. She wanted to be a momma.

This is great IF you have fertilized eggs and want chicks. I didn't think I had time or bandwith at the time so I tried to break her habits. Note, she does not lay eggs when she's broody, so we weren't getting any from her during this time. I gently took her off the nest multiple times a day and encouraged her to NOT brood, but to no avail.

Enter Issac.

A teammate was gifted a rooster one sunny Friday afternoon and he asked if he could "store" his rooster in our coop until....well, let's just say the plan was to have him go to the same place Handsome went...

I said sure, and another lightbulb went off. CHICKS!

I won't go into details, but suffice it to say all of the ladies produced fertilized eggs for at least 10 days, some for two weeks!

Another thing I learned - the momma hen actually doesn't produce fertilized eggs. Well, maybe she was fertilized, but she wasn't producing egs... therefore no fertilized eggs. She was already in broody mode, so her little hen body had stopped producing eggs when she went into "I want to be a momma" mode.

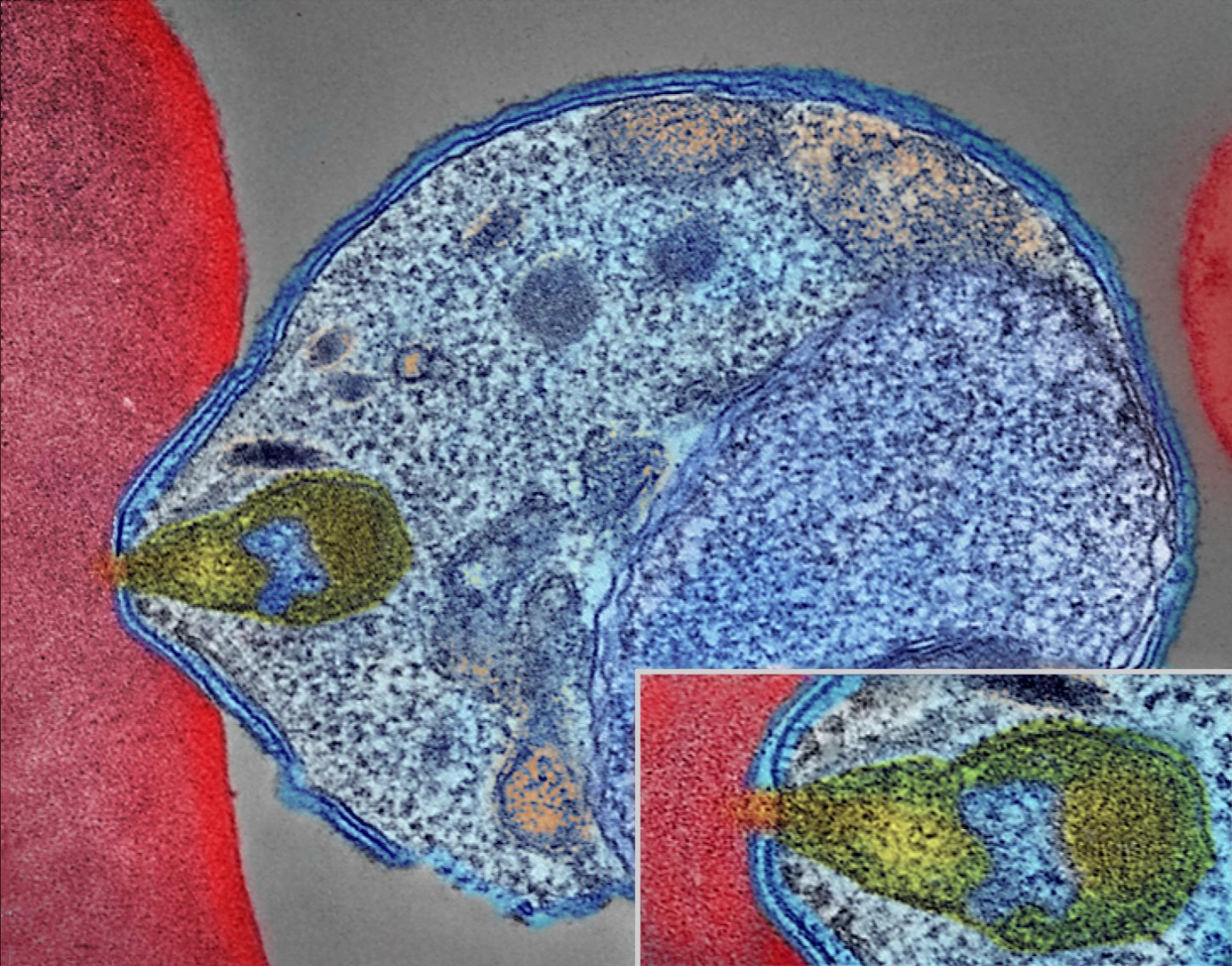

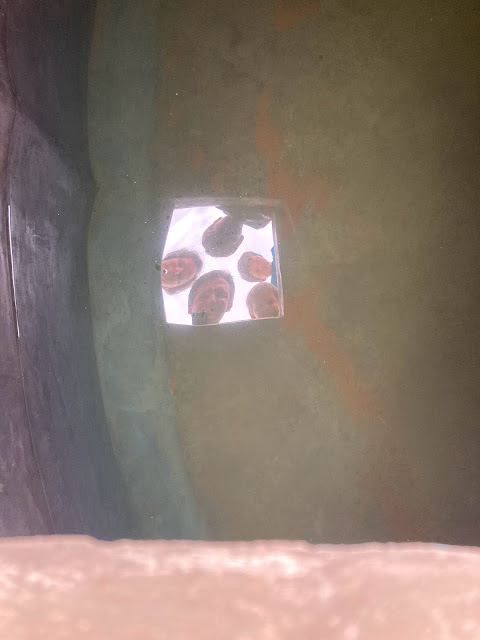

How do I know they were fertile? Well, I did a lot of reading (because - see first paragraph - I had NO idea what I was doing) and realized you could look in the yolk for a white dot with concentric circles starting to form. So that's what I did. Here's an example of one of the eggs I cracked 24 hours after Issac's arrival.

You'll see a tiny white dot - the egg is fertilized!

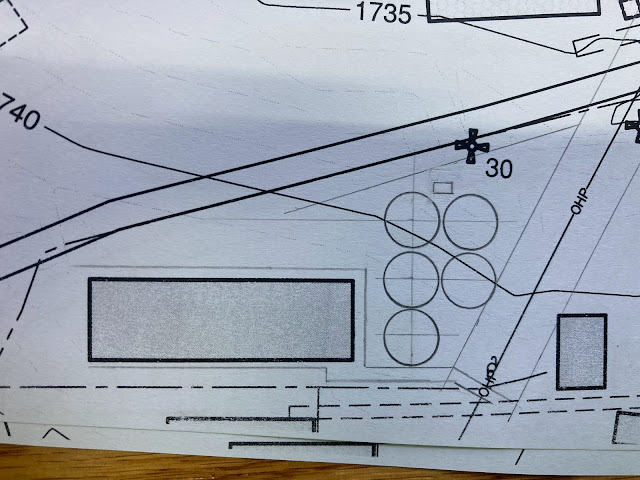

Since the ladies produce tons of eggs, and the momma can't sit on dozens, I marked some with a sharpie and let her continue to sit on those, while collecting and eathing the others that the other ladies were laying.

Something else I learned, you CAN eat fertilized eggs. They don't develop unless they are incubated.

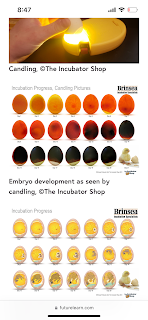

I also read about candeling - an essential step to see if your eggs are developing, or if she is just sitting on eggs that will become rotten. I didn't get a good picture of me doing it, but here's what candeling an egg each step of the way should look like.

Also - clearly I need more experience in this... see later in the story.

Twenty-one days went by (that's how long... or SHORT it takes for a chick to go from the picture you see above to a fully developed chick that can stand, eat, and drink just after it hatches! God's design is amazing!)

I let the momma incubate her eggs in the coop becuase I really didn't have another place to put her. Not ideal, but it worked.

The first chick "pipped" (made the first crack in the shell) one morning but when I came back it looked like the other ladies had started to peck at the chick in its egg. Not good - they will attack it and kill it. So I moved the momma, the hatching chick (who I didn't think was going to make it) into a bin and put the bin in our half bathroom with a space heater. Well, the chick made it! And was named Cookie. Then another one hatched the day after! They huddled under their momma and they were SO cute.

The first 5 chicks that hatched did really well and are still growing! Two other chicks hatched but they didn't survive, and three of the eggs didn't develop (hence my need for improving my candling skills. Despite the brief sadness of the two not surviving, we were thankful for the 5 that made it!

Once there were no more eggs to sit on, the momma hen was getting quite restless, standing up in the bin and trying to get out. So we moved them to the back portch. That lasted for a few days until they all started escaping the enclosure.

We decided to put the momma back outside where she could eat, drink, poop, scratch, and move about on her own terms.

And the chicks went back into the bin in the bathroom with the space heater.

They too started to get a little restless, and so we created a little enclosure inside the chicken run so that they could have their own outside space. Not pictured, but we created a little slatted door/gate so that they coudl get in and out of this little corner but the bit ladies could not.

They are super happy outisde!

They still come in at night and sleep in the bin.

Amelia, Madelyn, and Mark have LOVED this experience, and I have learned a lot on the way. And let's be honest, I've loved it too!

Touch base in a few weeks... maybe then we will know if they are cockrels or pullets! (We're hoping for 5 girls!)