(from Eric)

Something that initially surprised me about African medicine was the breadth and severity of blood disorders, the field which medicine calls Hematology. People's first guess is Infectious Diseases and, in particular, what we call "Tropical Diseases" (e.g. malaria, typhoid, tuberculosis and a host of crazy parasites like the Loa loa we diagnosed in a guy's eye this week). This is all true, but pretty much every field of medicine is dramatically affected by its context, and this seems particularly true of hematology in Africa.

I have come to accept as "not too bad" blood values that get you admitted to an ICU in the United States (which has been weird for me on at least two occasions when I have encountered such patients working the US on different leaves from Africa).

You can read here about some great old cases from Alyssa, including when she visited Burundi from Kenya, and our lowest-ever hemoglobin level from Rachel here. We have been astounded what people can live through and often wished for a hematology specialist to help us wade through the strange waters we're trying to navigate.

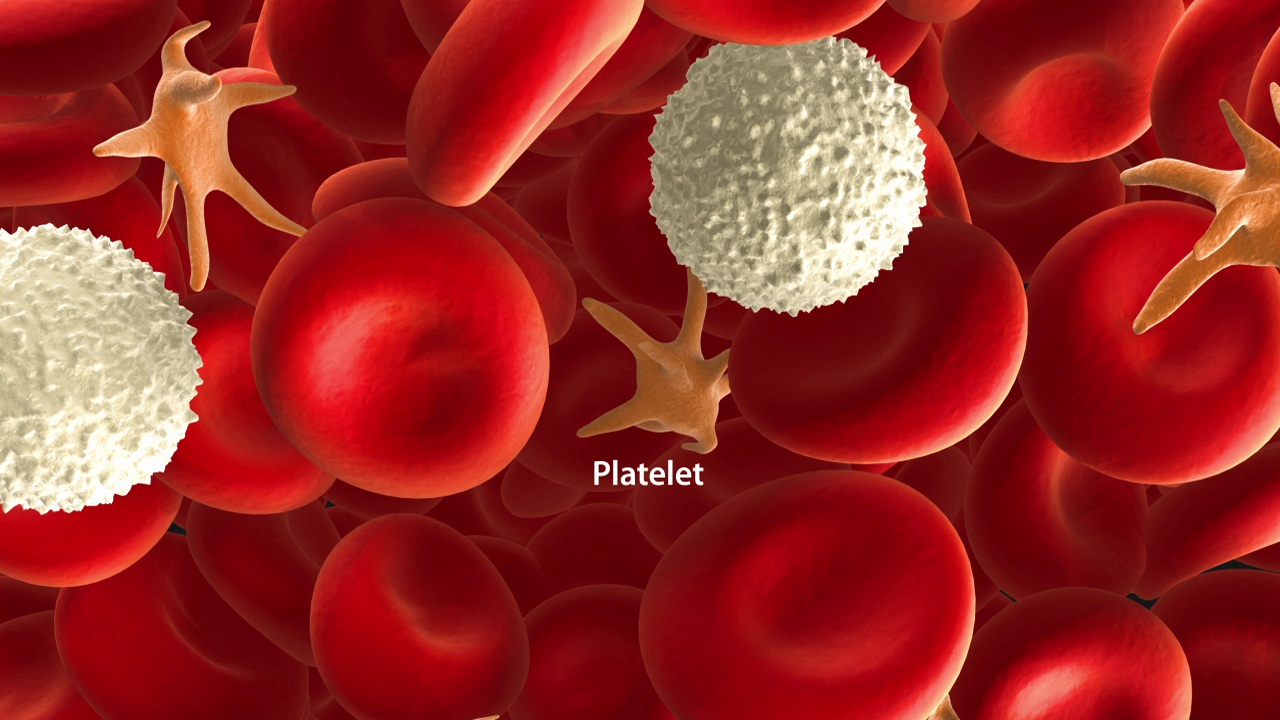

Last month we received a 22 year old young lady in our emergency room with a profuse nose bleed. In such cases that are bad enough for a Burundian to go to the hospital, we often find that their platelet count is low. Platelets are one of the blood components that are necessary for blood to clot. A normal count is somewhere north of 125-150. The average reader of this blog is likely somewhere around 300. When you get below 50, you can start to have trouble, and even more so if you get below 20.

This young woman's platelets were 2. I've seen <10 lots of times, but never 2. Well, of course, she's having trouble not bleeding. Carlan and his team went to work getting her immediate bleed under control, and with quite good effect, considering her low platelets. She was transfused, and the next morning, we rechecked her blood.

Now, her platelets were 1. Or maybe I should say her platelet was 1? Maybe we can't call it a platelet "count" at this point? Can you "count" to 1?

What to do? Her other blood components looked alright (except her red blood cells which were expectedly low given her hemorrhage), and so we were hoping that she had a condition called ITP, where your body forms antibodies against your own platelets, which causes them to be destroyed. Why did we hope this? Because we could treat it with steroids. There may be a lot of medicines that we can't always access, especially for severe blood diseases, but we have steroids.

We started her on treatment, and 3 days later, we checked her again, and her platelets were 13. Or as I liked to say: "13 times higher than before!!" This was still really low, but much better and well on her way to getting out of the immediate danger zone. Sure enough, her bleeding was soon well-controlled, and she was able to go home on pills with the chance to follow-up in clinic with hopes of a complete resolution.

***

On a related note, several years ago, Hope Africa University sponsored a young graduate named Dr. Ferdinand Nduwimana to go to specialty training in Senegal in what is called Biologie Médicale, which doesn't have an exact American equivalent, but is like a mix of laboratory medicine and non-tissue pathology. He returned to HAU several years ago, and has been helping greatly in the medical school in Bujumbura. He also comes up to Kibuye a couple times a month to work on developing our laboratory and its personnel, and to provide some advanced testing.

|

| Dr. Ferdinand growing our laboratory capacity |

Yesterday, when one of our intern doctors asked me about a guy from Tanzania who came with a white blood cell count of 342 (normal <10), I was delighted to see that Dr. Ferdinand happened to be around. His invaluable help showed us within hours what the likely diagnosis was, and how he might pursue further treatment in Tanzania, if possible.

***

For all that we cannot do, there is much to be thankful for.