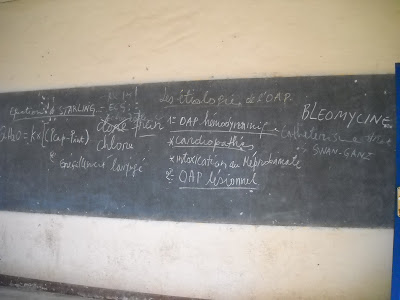

Why snap this photo? Well, without going into the medical details, I was both astonished and amused that in the middle of Bujumbura, on an old blackboard, students were being taught about relatively obscure treatments and invasive techniques that I was pretty such weren't available anywhere in the country. And years later, I can say that I was right: they're not available and possibly never were.

After years of medical school and residency in the US, and with about a year of African medicine (in Kenya) under my belt at that time, I had learned so much. We were looking forward to working in African medical education, and this blackboard struck me as the epitome of what we were going to better. We weren't going to teach archaic and inapplicable ideas to our students. We could do so much more.

***

Over the years, I have been surprised again and again by things I didn't understand. I remember the day years ago in the NICU at Kibuye when I realized that no one had any idea how to use the scale to weigh the babies. Weight gain in premature babies is truly a vital sign, fundamental to guiding what the doctor should do for the baby. I saw them randomly moving the weights of the balance around, and thought "what have I been doing for the past month?" (Obviously, the NICU has developed by leaps and bounds in the many years since I rounded there.)

Just yesterday, I was working on a small hospital project with some personnel and was again bowled over by my misplaced assumptions. In this case, I thought a certain person would certainly understand some particularly fundamental medical concepts. Nope. So I walked up and met with him for a while, trying to find out exactly where he was at, because it certainly wasn't what I had thought.

Fourteen years after moving to Africa, and I keep getting surprised at what I mis-guess or misunderstand. Each time, I learn a little more, but there is always something else that pulls the rug out from under me. Something else that I didn't understand and therefore I wasn't really engaging the situation correctly.

***

Today, I walked home from the hospital after some late afternoon teaching to our post-graduate interns on bleeding disorders. It had been fun. A new challenge to try and discuss a relatively complicated subject in an effective way, somehow reaching out across the void between me and them to connect.

I thought back to the Swan-Ganz catheter blackboard of 2010. Even now, I don't want to teach like that. I still believe we can do much, much better. But thirteen years later, I would say that sometimes there are reasons to teach things that are beyond the technology available around us. Sometimes students want to know, or maybe it's coming soon. Sometimes I find that a certain point may not be clinically relevant to them, but it can help illustrate a physiology concept in a useful way, so I try to use it to a different end. In other words, I think my approach to this question is more nuanced now.

I'm tempted to look back at my "one-year-in-African-medicine" self in 2010 and think that I didn't know anything then. But that's actually quite unfair. After years of training to become a physician attending, and a year in Kenya, I actually knew a lot. I had learned and learned and had my paradigms upturned and readjusted again and again.

It's just that I didn't realize how many more times I would keep learning. I didn't know how beyond one mountain there would always be another mountain. How I would just continue to be surprised and made to feel like I was back in month one over and over again.

It would be folly not to take this recollection and flip it forward. I suppose I will continue to be surprised. I wonder what I will know in five years that I understand more incompletely now. I think I can legitimately say that I've learned a lot, about medicine, about a totally different environment, about how to go about effecting needed change. But I'm also learning just how much more I have to learn.

***

PS. on a somewhat related note, Glory Guy's father Bobby has a healthcare business podcast and interviewed me over the summer. Click here for about 15 minutes of us chatting about how experiences here have shaped my lens on healthcare.